CSS Books & CSS Figures

Today we're happy to add two more specs to the WHATWG stable, Books and Figures! These are specifications focused on CSS features. Books provides ways to turn HTML document into books, either on screen or on paper. Using Books, authors can style cross-references, footnotes, and most other things needed to present books on screen or paper. Figures are also based on traditional publishing — it provides ways to float elements with respect to columns and pages, and describes how to wrap text around them.

Printing was part of the first CSS proposal in 1994, and many of these CSS features have been in use since the first paper book written in HTML and CSS (CSS — Designing for the Web) was published in 2005. Now, a decade later, bestsellers are routinely produced with CSS. There are currently two implementations of these specifications that are able to produce books: AntennaHouse and Prince. We hope that our continued work on these specifications will help existing implementations converge, and also encourage browsers to present web content as pages. Pages can be printed, stored as PDF files, or shown on screens. Many users will prefer pages to scrollbars, and these specifications will help make it happen.

As an example of a feature from Books, consider footnotes. Turning an element into a footnote is easy:

span.footnote { float: footnote }

This can, with a few more styles, be formatted as:

![Body text, with a superscripted footnote saying '[1]' in red, and under the body, a short line delimiting the body from text in a smaller font size, with the same red '[1]' indicating the footnote.](http://people.opera.com/howcome/2013/whatwg/books/footnotes.png)

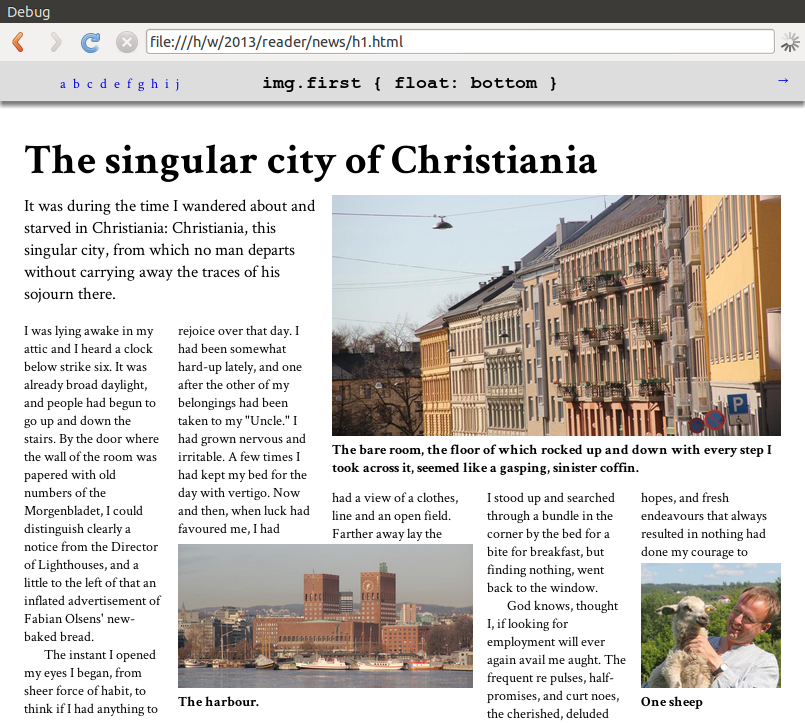

In another example, common newspaper and magazine layouts can be achieved with just a 10-line style sheet. Here's what this could look like:

More screenshots and code examples are available.

Feedback on these specifications, like all our others, is most welcome, either on www-style, on WHATWG's mailing list, or as bugs in the bug database.

The features described by these specifications were previously published as part of a W3C CSS working group document that I wrote. Today we are moving the work to WHATWG, a W3C Community Group.

Can you share more regarding “Today we are moving the work to WHATWG, a W3C Community Group”? How does this benefit the drafts? Wouldn’t they typically benefit from being reviewed and endorsed by the CSS WG?

Yay, congrats! HTML, DOM & CSS! What’s next? HTTP?

The WHATWG welcomes feedback from all sources, including members of the CSS working group (like myself). In practice, though, review for all specs, whether published at the W3C or the WHATWG, comes from Web developers and implementors (e.g. AntennaHouse and Prince); the actual place where the document is published doesn’t affect that.

There are some important benefits to publishing the spec in WHATWG. The “living standard” model allows quick updates with little overhead; in the past is has proved difficult to publish W3C WDs in this area. WHATWG’s goal of keeping “the specifications a little ahead of the implementations but not so far ahead that the implementations give up” (FAQ)is one that I strongly believe in.

What about the IP implications of moving work out of the W3C?

Thanks Håkon. I think the problem we’re running into now (also with HTML) is one of spec fragmentation… but that’s also a discussion to be had elsewhere.

@jens

right, in regards to HTML spec fragmentation as neither the whatwg nor w3c has the support of all the various stakeholders and its not something that can be claimed/mandated or argued from authority. The best we can do is keep the differences to a minimum.